Quick Answer: Prickly pears are generally illegal in Australia due to their potential to cause ecological harm, the species Opuntia ficus-indica is the sole exception. This species is permitted under controlled conditions because of its less invasive nature and value as a versatile agricultural crop. Read on for a much deeper dive into this prickly problem.

In Australia, the prickly pear cactus is controversial due to the widespread devastation certain species have caused and continue to cause, particularly to farmers.

The weed potential of the Prickly Pear cactus in Australia is so great that all 150+ species of opuntioid cacti have been declared Weeds of National Significance at a federal biosecurity level. In addition, every state & territory has individually outlawed their possession, cultivation and sale.

The only exception is the Opuntia ficus-indica (Spineless Prickly Pear), which we will explain later in this article.

The Arrival of Prickly Pears in Australia

In the late 1700s, during the early days of the First Fleet’s arrival in Australia, prickly pear cacti were introduced. These plants, likely Opuntia monacantha, were brought on one of Captain Arthur Phillip’s ships. Originating from Brazil, the cacti came infested with cochineal insects (Dactylopius coccus), which were known for producing a valuable dye.

The Cochineal Dye Industry

Before synthetic dyes emerged in the late 19th century, crushed cochineal insects were used to create the most vibrant red dye available. This dye had been a staple in North and Central America for hundreds of years, and when the Spanish conquistadors arrived in 1519, they instantly saw its value. Spain quickly established a monopoly on cochineal dye in Europe, and it became a significant export from Mexico, second only to silver.

In the modern world, it’s hard to fathom just how valuable this new dye was. Red was associated with power and prominently used in the robes of kings and cardinals and the British army’s redcoat uniforms. This lucrative market caught Britain’s attention, and Joseph Banks proposed the establishment of a cochineal dye industry in New South Wales, Australia, in the late 18th century.

Although the industry never really took off, and the cochineal insects soon died off, their food source, the prickly pear cacti, continued to grow and spread at an alarming rate.

Spread and Impact

The initial prickly pear, Opuntia monacantha, did not expand much beyond the eastern coast. However, during the mid-1800s, various other prickly pear species were introduced to Australian gardens. Settlers used them as hedges and animal fodder during droughts, as the plants thrived in the arid conditions west of the Great Dividing Range. Notably invasive were the common pest pear (Opuntia inermis) and the spiny pest pear (Opuntia stricta).

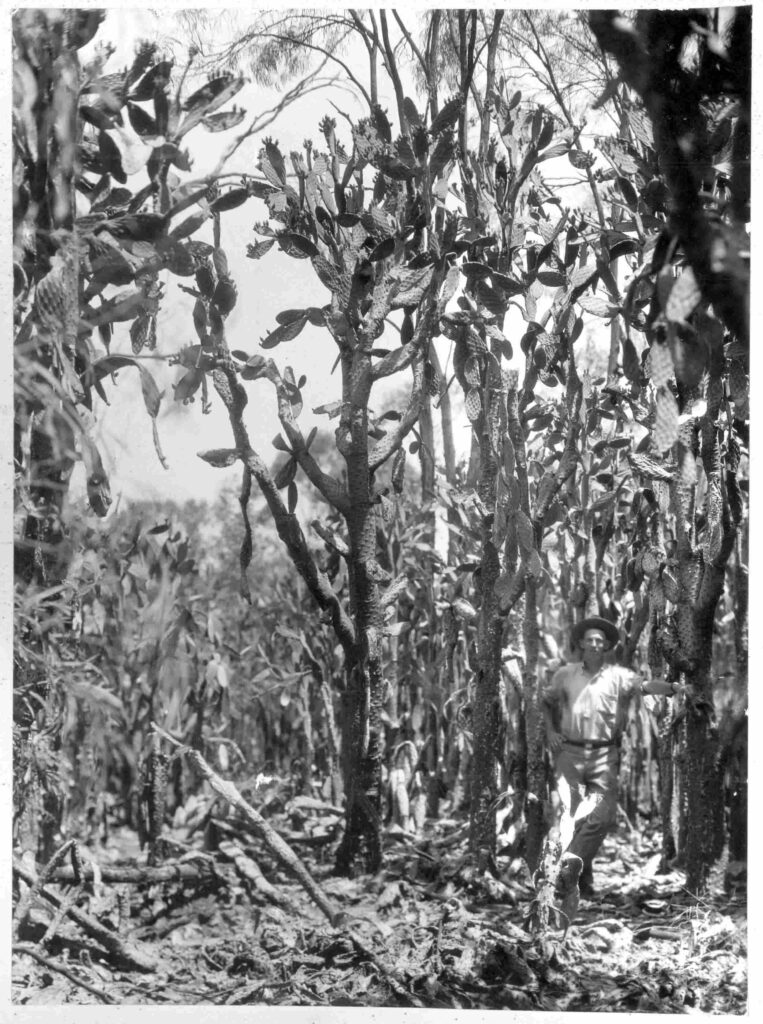

These cacti spread prolifically, sometimes covering whole valleys and hillsides in a single growing season. This had a massive impact on farmers whose fields were being invaded by Prickly Pear, and whose livestock could no longer graze freely and safely. Some Opunti species, particularly the Opuntia stricta, have long, sharp spikes which cows can’t break down. Consumption would eventually lead to catastrophic damage to the cows mouth and throat, which would remove their ability to eat, eventually leading to starvation.

Government Response

The first major governmental response to the prickly pear problem was the Prickly-Pear Destruction Act in 1886 in New South Wales. This law mandated landowners to destroy the plants on their properties and established the first government inspectors for enforcement.

Despite this, prickly pear continued to spread. The Queensland Government offered a £5,000 reward in 1901 for a practical eradication method, which was increased in 1907, but no successful method was found. Techniques such as burning, digging, crushing, and poisoning were employed but proved largely ineffective.

By 1926, large quantities of arsenic and other poisons had been used, yet these labour-intensive methods still did little to control the spread. Many areas were rendered unfit for farming, and leasehold lands were abandoned.

By the early 20th century, the Australian government recognized the urgent need to control these invasive species. Large-scale eradication efforts were launched, which finally found some success in the prickly pear moth (Cactoblastis cactorum).

In 1913, a Queensland Travelling Commission was established to investigate biological controls for prickly pear. The Commission’s research revealed that prickly pears were naturally attacked by various insects and diseases in their native range. The most promising of which was the cactus moth (Cactoblastis cactorum) which showed great promise in consuming the plants. However, World War I delayed further action.

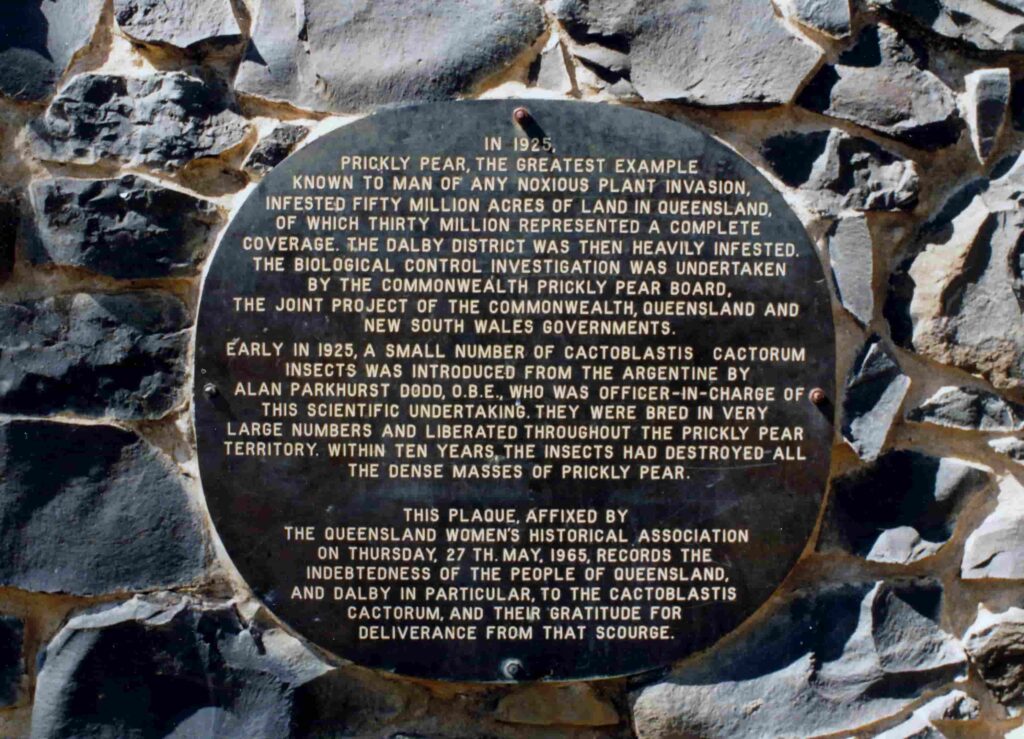

In 1920, the governments of the Commonwealth, Queensland, and New South Wales banded together to form the Commonwealth Prickly-Pear Board (CPPB) to explore these biological control options. The Board sent entomologists to the Americas to acquire biological agents and set up a breeding centre for the cactus moth (Cactoblastis cactorum) in Queensland.

The Cactoblastis Moth

Cactoblastis cactorum – what a great name, huh? The cactus moth, native to Argentina, lays its eggs on prickly pear plants. The larvae consume the cactus tissue, potentially destroying entire plants within weeks. After maturing, the larvae pupate, and the cycle begins anew.

Initial attempts to propagate the moths in the 1920s failed, but eventually, 3,000 eggs were imported from Argentina and effective numbers were produced. By 1926, the moths were released in Chinchilla, Queensland. The moths proved highly effective, with up to 14 million eggs distributed daily. By 1933, most overgrown areas had been cleared of prickly pear.

To this day, the introduction of the Cactoblastis cactorum remains one of the only known examples of a time when humans introduced a biological control agent which didn’t have any known adverse flow-on effects. Typically, when biological controls are introduced, it just leads to new problems: “swallow the spider to eat the fly”, but in the case of Cactoblastis cactorum, these moths don’t seek out any alternative food sources. So when the cacti are abundant, the moths have a lot to eat and multiply rapidly, and when the cacti die out, so do the moths.

Legal Status of Prickly Pear Species in Australia

Due to their invasive nature, most species of prickly pear continue to be restricted under Australian biosecurity laws. The legislation is designed to prevent the introduction and spread of non-native species that could threaten the country’s unique flora and fauna.

Out of the 150 or more prickly pear species, all are illegal in Australia except for one: the Indian fig (Opuntia ficus-indica). This species has been deemed less invasive & destructive than its criminal cousins.

Click the below links to read official bio-security information relevant to the state or territory you live in:

Australian Capital Territory (ACT)

Why Opuntia ficus-indica Gets An Exception

Opuntia ficus-indica, also known as the Spinless Prickly Pear, Indian fig or Barbary Fig, is distinct from other prickly pears in several ways. As its name suggests, it has no or very few true “spines”. However, gardeners beware, as it still contains glochids, tiny hair-like spines that make you want to peel your skin off when you get stuck by them.

Unlike other prickly pears that spread aggressively and displace native species, the Indian fig is less prone to causing such ecological damage. It doesn’t propagate and spread from cuttings quite as prolifically, and its seeds are typically less fertile.

It is cultivated in Australia primarily for its fruit, which is used in various culinary applications and traditional medicine.

However, it is still subject to regulation in some states to prevent its potential spread beyond intended cultivation areas. So whilst you won’t be breaking the law by keeping an Opuntia ficus-indica as a house plant, if you want to start a farm you will likely need to still get approval from your State’s bio-security department.

Play it Safe

Many backyard growers and small farmer’s market sellers are selling illegal and invasive varieties – from our experience, often unknowingly. So if you’re looking to add a prickly pear cactus to your collection and are worried about accidentally getting the wrong type our advice is to always play it safe and only purchase prickly pear from reputable vendors where the species is communicated. If you ask the seller if it’s the legal variety, and they can’t give you a straight answer, just stay away. The ecological damage and the fines for possession are simply not worth it.

Do we sell Opuntia ficus-indica?

No, not currently. But we may in future, so watch this space.